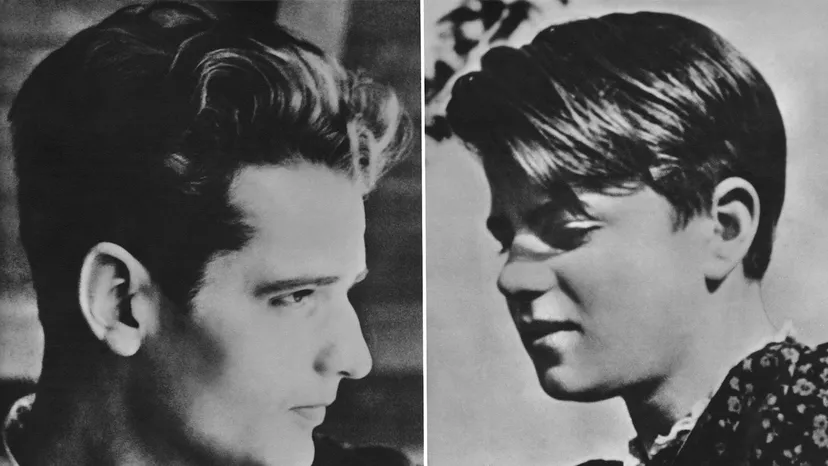

L-R: Hans Scholl, his sister Sophie Scholl and their friend Christoph Probst are photographed in 1943.

On February 18, 1943, during the height of World War II, two German college students from the University of Munich entered one of the main campus buildings, walked to the top of a staircase, and threw a stack of leaflets over the banister and down. in the crowded lobby. The leaflet, the sixth in a series of clandestine publications by a group calling itself the White Rose, urged fellow students to rebel against Adolf Hitler and the Nazi war machine.

“The Day of Reckoning has arrived,” said the White Rose pamphlet, “the reckoning of our German youth with the most despicable tyranny ever endured by our nation… Students! The German people are looking at us!”

The two students who abandoned the leaflets at the University of Munich were grabbed by the janitor and handed over to the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police. They were brothers, Hans and Sophie Scholl. And within days, Hans and Sophie, and their friend Christoph Probst, were convicted of treason and executed. Many of his co-conspirators in the White Rose resistance movement were executed in the months that followed.

Today, the name Sophie Scholl is synonymous in Germany with courage, conviction and the inspiring power of youth. At just 21 years old, Sophie fought against a murderous regime – not with guns and grenades, but with ideas and ideals.

Content

- The awakening of a 'Hitler Youth'

- Leaflets call for passive resistance and sabotage

- 'They knew the danger and chose to act'

- A life interrupted and a legacy of resistance

The awakening of a 'Hitler Youth'

Sophie was born into a Christian family in 1921. She was 12 years old when Hitler and his National Socialist Party came to power. Like her schoolmates and siblings, she avidly participated in Nazi-run youth programs, the Hitler Youth for boys and the German Girls' League for girls, even though her parents were critical of the Nazi party. With her enthusiasm and leadership skills, Sophie quickly rose through the ranks.

However, when Sophie graduated from high school, Germany was at war and two of her brothers and her boyfriend had been called up to fight. The joyful patriotism of their youth was replaced by heartache for the young men dying at the front, fear for their family and friends, and contempt for the fascist police state that controlled every aspect of their lives.

Intelligent and ambitious, Sophie wanted to study biology and philosophy at university, but was forced to work for a year in the National Labor Service, where she opposed the military regime and mind-numbing tasks. In her diary entries and letters to her boyfriend, we get a glimpse of a young woman who longed for peace and freedom.

“In these documents, we can trace Sophie's development from a child to a caring young woman,” says Hildegard Kronawitter, president of the White Rose Foundation in Munich. “The closer we get to her, the more we are impressed by her thinking and strong opinions.”

Leaflets call for passive resistance and sabotage

In 1942, Sophie enrolled at the University of Munich, where her older brother Hans was already studying medicine. Hans and his friends were recruited as doctors on the Eastern Front and witnessed atrocities such as the mass murder of Polish Jews and the needless deaths of countless German soldiers.

Unable to contain their anger at Hitler's criminal regime, Hans and a small circle of like-minded friends formed the White Rose in June 1942 and began publishing and distributing clandestine pamphlets calling on ordinary Germans to rise up against Nazism.

“Which of us can judge the extent of the shame that will fall upon us and our children when one day the veil falls from our eyes and the cruelest crimes, infinitely beyond measure, come to light?” wrote Hans and his friend Alexander Schmorell in the first leaflet. “Therefore, each individual must resist in this last hour as much as he can, conscious of his responsibility as a member of Christian and Western culture, must work against the scourge of humanity, against fascism and all similar systems of the absolute state.”

In the second leaflet, Hans and Schmorell rightly called the mass murder of Polish Jews in German concentration camps “the most terrible crime against human dignity, a crime for which there is no comparison in the entire history of mankind.”

And in the third leaflet, the White Rose urged normal Germans to commit secret acts of sabotage wherever they worked: in munitions factories, government offices, newspapers, universities – “each of us is capable of contributing something to overturning this system ”.

Sophie joined her brother in the White Rose resistance and helped publish and distribute the leaflets throughout Munich and other German cities, which was not easy due to wartime rationing and travel restrictions. “Please double and pass on!!!” he begged for the third leaflet, hoping that it would reach the hands of more Germans who opposed the regime.

'They knew the danger and chose to act'

In 1943, Sophie and the other members of the White Rose felt that the tide of war had turned against Germany. During the disastrous Battle of Stalingrad in late 1942, Germany lost a staggering 500,000 soldiers. The White Rose began taking bolder steps to incite a disillusioned public to action.

The group painted graffiti all over Munich with the words “Freedom” and “Down with Hitler”. And instead of sending out their flyers in secret, they decided to hand them out in person on campus.

“I wouldn't say they were overly idealistic and didn't understand the danger of what they were doing,” says Kronawitter. “They knew the danger and chose to act anyway.”

The leaflet that Sophie and Hans rained down on the crowded atrium was the sixth leaflet, written by one of their teachers, Kurt Huber, and it ended with this hopeful exhortation: “Our nation is about to rise up against the enslavement of Europe through National- Socialism, in the new and devout advance of freedom and honor!”

A life interrupted and a legacy of resistance

When Sophie was arrested, she first denied any connection to the pamphlets or the White Rose, but once Hans admitted his role, she too confessed.

“We were convinced that Germany had lost the war and that all the lives sacrificed for this lost cause are sacrificed in vain,” Sophie told her interrogators. “The sacrifice demanded at Stalingrad especially led us to undertake something in opposition to the (in our opinion) senseless bloodshed… I knew immediately that our conduct was intended to put an end to the current regime.”

Sophie and Hans attempted to protect the other White Rose conspirators by claiming that the two of them were solely responsible for writing the pamphlets, but their friends were eventually drawn into the investigation and suffered the same cruel fate, death by guillotine. The other White Rose members executed by the Nazis were Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, Kurt Huber and Christoph Probst.

A notable artifact of Sophie's trial and conviction is a document she received that lays out the state's case against her. On the back, Sophie wrote the word “ Freiheit ” or “Freedom” in a decorative script.

“I think this is really moving,” says Kronawitter. “Here she was in prison and had just been informed that the prosecutor was demanding the death sentence. And after she read this, her response was 'freedom'.”

Among Sophie's final words before she was taken away for execution were: “It's such a splendid sunny day and I have to go. But how many have to die on the battlefield these days, how many young and promising lives. What does my death mean if by our actions thousands are warned and alerted.”

It turns out that the sixth leaflet escaped Germany and made its way to the UK and the US, where exiled German author Thomas Mann praised the members of the White Rose, saying: “Well done, splendid young people! You will not have died in vain; you will not be forgotten. […] A new faith in freedom and honor is emerging.”

Now that's cool

The 2005 film "Sophie Scholl: The Last Days" was nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, and many streets, squares and schools in Germany are named after Sophie, where she is celebrated as a folk hero.